For almost two decades, the China plus one strategy was seen as a smart hedge. Companies kept their main production base in China, then added a secondary country somewhere in Asia as a safety valve. It was a backup plan, not a complete redesign.

By 2026, that mindset is no longer enough. Global sourcing is being reshaped by energy instability, geopolitical risk, AI-driven planning tools, and growing pressure around ESG and compliance. Executives are no longer asking “Should we diversify our supply base out of China?” The real questions have become: How fast can we diversify? Which alternative manufacturing countries make sense for our product category? And how do we build a multi-country network that is resilient, fast, and flexible, not only cheap?

Recent research from Prologis, based on a survey of more than 1,800 senior executives in the US, Europe, Asia, and Mexico, confirms that global supply chains are going through the biggest reset in a generation. Energy reliability, spee,d and location are now seen as the three decisive variables shaping supply chain strategy for the next decade.

In this blog, we look beyond the basic China plus one strategy and explore how leading companies are building multi-node manufacturing networks for 2026. We’ll also examine the role of Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia as the four key alternative manufacturing countries in Southeast Asia, and outline a practical roadmap for buyers who want to diversify without losing control of quality, cost, or timelines.

Why The Classic China Plus One Strategy Is No Longer Enough in 2026

For many years, the story was straightforward. China offered scale, infrastructure, and an integrated supplier ecosystem that no other country could match. The default playbook was to manufacture in China, ship globally, and focus on unit cost and lead time.

When trade tensions, tariffs, and pandemic-era disruptions began to accumulate, the China plus one strategy emerged. Companies kept their main capacity in China but added a second country as a contingency, often in Southeast Asia. This solved part of the problem, but not all of it.

Several structural shifts have now turned China plus one into a starting point, not a destination. Energy instability has become one of the top concerns for supply chain operators. In the 2026 Prologis Supply Chain Outlook, almost nine in ten companies reported some form of energy disruption in the previous year, from price spikes to weather-driven outages when your factory can’t keep the lights on, having the lowest labor cost suddenly doesn’t matter.

Policy and trade risk remain high. Export controls, sanctions, technology restrictions, and shifting tariffs keep adding uncertainty to long, single-country dependent supply chains. One regulatory change can ripple through an entire product line if all your production sits in one jurisdiction.

Sustainability and ESG pressure mean buyers need deeper visibility into working conditions, emissions, and material sourcing across the entire chain, not just their tier-1 suppliers. Customers, regulators, and investors are all asking harder questions, and “we don’t know” is no longer an acceptable answer.

Digitalization and AI allow companies to monitor performance and risk in real time. This makes it easier technically to orchestrate production across several countries instead of one. What was once a logistical nightmare is now a manageable challenge with the right tools.

In this environment, relying on one primary country plus a small backup is simply too fragile. Resilience in 2026 requires networks, not single points of failure.

This video explores why a new manufacturing hub is emerging as a key alternative to China in the coming years.

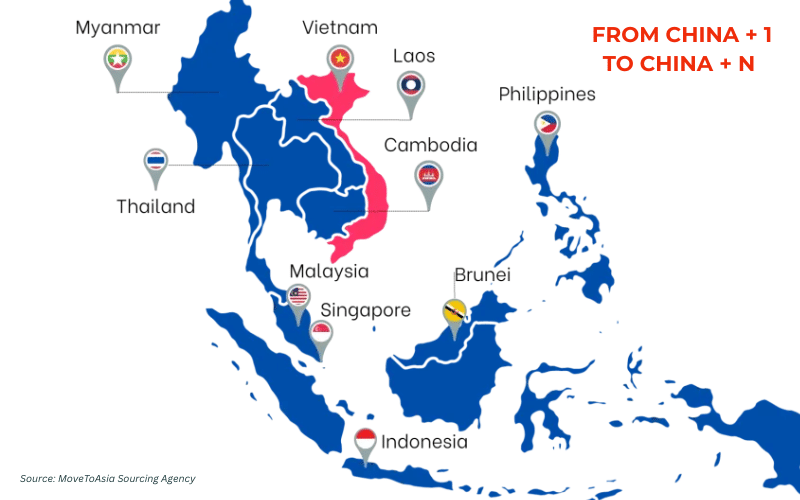

From China Plus One To China +N: Supply Chain Diversification as a Portfolio

Instead of treating manufacturing as a single, static choice of country, leading companies now treat their footprint like a portfolio. The idea is similar to financial diversification: no single asset should be able to derail the whole system.

In practice, China +N means keeping strategic capacity in China where it still makes sense, adding one or more alternative manufacturing countries for specific categories, and spreading risk across several regions, not just several suppliers in the same place.

Prologis and The Harris Poll report that business leaders are redefining supply chain strategy around three pillars: AI adoption, regional self-sufficiency, and energy resilience. A growing share of executives expect their networks to become more localized and multi-regional by 2030, instead of being dominated by one global hub.

The logic is clear. If one country faces tariffs, you shift volume elsewhere. If one region suffers a power crisis, you can lean on plants in a more stable zone. If freight lanes are disrupted, regional manufacturing can still serve nearby markets.

The keyword for manufacturing diversification in 2026 is not replacement, it’s balance. China remains a critical part of the picture, but as one node among many, not the only pillar holding everything up.

What The 2026 Outlook Data Reveals About Global Sourcing

The Prologis 2026 Supply Chain Outlook and similar studies give us a useful snapshot of how leaders are thinking. Several patterns stand out, and they paint a picture of an industry that’s learning from recent pain points.

Energy reliability is now a top selection factor. According to Prologis, around seven in ten executives fear power outages more than any other form of disruption, and many say they are willing to pay a premium for sites with reliable energy infrastructure. This is remarkable—for decades, energy was assumed to be stable and cheap. Now it’s a decision-making variable that can trump labor cost in certain scenarios.

Resilience beats pure cost. The survey highlights that companies are increasingly ready to trade a small uplift in unit cost for more stable capacity, better energy security, and faster reaction times. This represents a fundamental shift in how procurement teams are measured and rewarded. It’s no longer just about squeezing the lowest price per unit; it’s about the total cost of ownership, including the cost of disruption.

Regional networks are becoming the norm. A large majority of respondents plan to build or expand regional, self-sufficient supply chains that place production closer to end markets, instead of relying on a single long transcontinental route. This doesn’t mean abandoning global trade—it means redesigning it to be less brittle.

In other words, manufacturing diversification in 2026 is not just a buzzword. It’s translating into concrete decisions on where to build plants, which ports to use, and which countries to trust as long-term partners.

The Three Strategic Pillars Of Sourcing In 2026

The survey results and the broader conversation in the industry converge on three core ideas that define the new era of global sourcing: resilience, speed, and flexibility. These three pillars are the filter through which buyers now evaluate locations and suppliers.

Resilience: Turning Shock Protection Into A Design Principle

Resilience used to be seen as “nice to have” insurance. Today it’s a design principle. For international buyers, that means using multi-node sourcing instead of single-country sourcing for critical product lines, having backup plants and alternative ports ready to go, and looking seriously at energy stability, regulatory environment, and political risk when choosing new sites.

In a resilient system, a trade dispute, a new tariff, or a regional power outage is unpleasant, but not fatal. Volume can be reallocated. Contracts and logistics arrangements are already in place. You don’t have to scramble in crisis mode; you execute a plan you’ve already stress-tested.

Speed: From Lead Time To Implementation Time

Speed is often misunderstood. It’s not only about cutting transit time by a few days. In 2026, speed also means how quickly you can bring a new supplier or country online, how fast you can ramp up production when demand spikes, and how long it takes to redesign logistics around a new destination market.

Regionalization strategies support this. When companies shift from a single global hub to multiple regional production networks, they reduce shipping time, but they also get closer to end markets and can respond more dynamically to changing demand patterns. Delays now hit competitiveness directly. When lead times stretch from weeks to months, buyers lose shelf space, market share, and cash flow. This is why so many executives link speed with strategic advantage, not just operational efficiency.

Flexibility: Building A Network, Not A Cage

Flexibility is the ability to pivot when conditions change. In the context of manufacturing diversification, this looks like having the option to move labor-intensive steps to a lower-cost country when wage pressure increases, the ability to increase capacity in a market that is geographically closer to key customers, and access to specialized factories that can handle certain technologies or quality levels better than others.

Shifting from a single-country to a multi-node manufacturing network is now the dominant trend. Companies are no longer asking which country is “best”. They’re asking which combination of countries gives them the best balance of cost, speed, resilience, and quality for each product family. That’s a much more sophisticated question, and it requires a more sophisticated answer.

The New Manufacturing Map: Four Key Alternative Countries Beyond China in 2026

For many buyers, the question is no longer “China or not China”, but “If China remains one pillar of my supply chain, which other pillars should I add?”

In Southeast Asia, four alternative manufacturing countries are attracting particular attention in 2026: Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. Each plays a different role in a diversified strategy.

Vietnam: The Anchor Of Many China Plus One And China +N Strategies

Vietnam has grown from a niche low-cost producer into a mainstream manufacturing hub for electronics, textiles, furniture, consumer goods, and more. Several factors make Vietnam especially attractive right now.

Competitive labor for labor-intensive production is still a major draw. Wages are generally lower than in coastal China, while the industrial workforce has experience in assembly, packaging, and light engineering. It’s not just cheap, it’s capable.

Three strong industrial clusters give buyers options. The North around Hanoi and Hai Phong, the Central region around Da Nang, and the South centered on Ho Chi Minh City and surrounding provinces each offer industrial parks, ports, and a deep subcontracting network. This means you’re not locked into one geography within the country.

Growing export and FDI base shows momentum. Vietnam’s exports and manufacturing FDI have grown steadily, helped by participation in agreements such as CPTPP and RCEP that connect it to key global markets. When other companies are investing and scaling, that’s usually a sign that the infrastructure and business environment are moving in the right direction.

For many categories, Vietnam is the “best bang for the buck” option in 2026. It’s suitable for labor-intensive products that benefit from experienced operators, scalable enough to support mid-size and large brands, and close enough to China to import components and raw materials while gradually building more local sourcing.

There are, however, some structural challenges that buyers must factor in. Logistics costs are often higher than in China, especially for inland factories. Many raw materials, especially for higher-tech production, still need to be imported. And for some high-tech segments, such as advanced semiconductors, Vietnam is still emerging, not yet a leader.

This is where working with a local sourcing partner becomes essential. On-the-ground teams can help buyers select the right clusters, negotiate realistic pricing, and build a quality control system that fits long-term growth plans. Without that local knowledge, you can easily end up in the wrong industrial zone or with suppliers who promise more than they can deliver.

Malaysia: High Tech, High Quality, Strong Infrastructure

Malaysia positions itself differently. It combines relatively high English proficiency, strong technical skills in several high-value sectors, and a longstanding investment in electronics, semiconductors, and advanced manufacturing.

As a result, Malaysia is a compelling alternative manufacturing country for high-tech components and sub-assemblies, precision engineering and automated production lines, and projects where uptime, energy stability, and quality are more critical than the absolute lowest labor cost.

The trade-off is clear. Labor costs are higher than in Vietnam, and scaling up quickly can be more complex. Policy changes and cost of utilities can also shift more rapidly. But for buyers looking to diversify into a country that is already deeply embedded in electronics and high-value manufacturing, Malaysia often sits high on the shortlist. You’re paying for stability and capability, not just hands on an assembly line.

Thailand: Automotive And Complex Industrial Components

Thailand has built a reputation as a leading automotive and mechanical components hub in Asia. It offers skilled workers in machine parts, automotive parts, and complex assembly, a mature ecosystem of industrial estates and logistics providers, and strong road networks and ports that support regional and global exports.

For buyers in automotive, industrial equipment, or engineering-heavy sectors, Thailand is often evaluated as a complement to China or Vietnam. The main constraints are similar to Malaysia—labor and operating costs that are higher than neighboring low-cost countries, and limited ability to add very large new capacity in a very short time frame.

However, when quality, precision, and mature logistics are critical, Thailand provides a reliable pillar in a China +N network. It’s not trying to be the cheapest option; it’s trying to be the most dependable for complex work.

Indonesia: Scale, Resources, and Selective Category Opportunities

Indonesia is different again. It’s a vast archipelago with a large population, abundant natural resources, and growing manufacturing capacity. Its strengths include the availability of raw materials such as rubber and certain metals, a large labor pool for labor-intensive sectors like textiles and footwear, and attractive cost levels in many industrial zones.

At the same time, there are important constraints. Being an archipelago means more complex domestic logistics and potentially higher internal transport costs. Infrastructure and adoption of the most advanced manufacturing equipment are still uneven across regions.

For this reason, Indonesia may not be the first choice for very high-tech or highly automated production in 2026. But for categories that match its strengths, such as certain types of consumer goods or raw material-intensive products, it can play a valuable role in diversifying away from China while keeping costs competitive. The key is matching product to place, not forcing a fit that isn’t there.

How Global Buyers Are Redesigning Their Sourcing Strategy For 2026

Knowing the trends and country profiles is one thing. Turning that into a concrete plan is another challenge. In practice, successful manufacturing diversification in 2026 follows a clear sequence. Let’s walk through what that looks like.

Map Your Risk And Exposure

Before selecting new countries, leading companies start with a simple question: Where are we overexposed today? That involves mapping current production volumes by country and by supplier, identifying single points of failure in the chain (one factory, one port, one key component source), and flagging products that are critical to revenue or brand reputation.

This risk map then guides where diversification will have the biggest impact first. If 80% of your revenue comes from products made in one industrial park in Guangdong, that’s your red zone. If you have backup capacity in three countries for low-margin commodity items but nothing for your hero product, you know where to focus.

Design A “Country Portfolio” Instead Of A Single Bet

Next, companies design a portfolio of countries that play different roles. For example, China might remain the main hub for high-volume mature products with stable demand. Vietnam becomes the primary alternative for labor-intensive products and certain electronics. Malaysia or Thailand handles higher-tech or precision-driven components. Indonesia is used selectively where raw material advantages exist.

The goal is not to be present everywhere. It’s to match product categories with the alternative manufacturing countries that can produce them well at scale, while reducing overall risk. Think of it like building a sports team; you want specialists in each position, not five people who can only play center.

Shortlist, Vet, and Visit Suppliers

Once the country portfolio is sketched, buyers move on to supplier identification and vetting. This usually includes market scanning to identify factories that match the required certifications and capacity, document checks including business registration and quality certifications such as ISO 9001, and factory audits to check equipment, processes, social compliance, and management culture.

In 2026, companies put increasing weight on energy reliability and backup systems, ESG and social compliance credentials, and the ability to support digital integration and data sharing. These aren’t nice-to-haves anymore, they’re deal-breakers. A factory that can’t share real-time production data or doesn’t have a credible sustainability roadmap is going to struggle to win business from sophisticated buyers.

Pilot First, Then Scale

Diversification doesn’t mean moving everything overnight. A common practical path is to start with one or two SKUs or a limited production batch in a new country, run thorough quality control and logistics tests, compare landed cost and lead time with the existing setup, and scale up gradually as confidence grows.

This approach reduces risk while giving buyers concrete data on what works in each location. You learn what the real lead times are, where the quality issues pop up, and whether the logistics math actually works once you factor in all the hidden costs. Better to learn those lessons on a pilot than on your entire product line.

Strengthen Your On-The-Ground Capabilities

Finally, companies that succeed with China +N rarely manage everything remotely from the head office. They either build their own small local teams in key alternative manufacturing countries or they work with specialized sourcing agencies that already have people on the ground.

For example, a partner like MoveToAsia can scout and benchmark factories in Vietnam and across Asia, conduct audits and joint visits with your team, oversee quality control and pre-shipment inspections, and coordinate ramp-up and help solve issues that appear once real production starts.

This local presence is what transforms a theoretical diversification plan into a long-term, resilient sourcing platform. Without boots on the ground, you’re flying blind, and in 2026, that’s a risk very few companies can afford to take.

What This New Era Means For Vietnam And Your China +N Roadmap

Vietnam deserves a special mention in the China +N conversation because it sits at the intersection of cost competitiveness, scalability, and long-term potential. In 2026 and beyond, many global buyers will keep a portion of their manufacturing in China (especially for complex supply chains that still depend heavily on Chinese components), move labor-intensive or mid-complexity products to Vietnam to balance cost and risk, add Malaysia or Thailand for certain high-tech or precision segments, and use Indonesia selectively where its raw material base and labor cost profile fits.

In that architecture, Vietnam often becomes the first alternative manufacturing country to test, for several reasons. It already has strong FDI inflows from Asia, Europe, and North America, which has built a broad industrial ecosystem. Its geographic proximity to southern China makes it easier to keep some parts of the ecosystem connected. And its young workforce and dense network of industrial parks make it easier to scale up once a pilot succeeds.

For buyers, the question is not “Should we move everything to Vietnam?” It’s “Which part of our product portfolio fits Vietnam best in the next 3 to 10 years, and how can we structure that move in a way that supports resilience, speed, and flexibility?”

Key Takeaways For Sourcing And Procurement Leaders

As you look ahead to 2026, a few conclusions stand out clearly:

The traditional China plus one strategy has evolved into China +N. Resilience, not cost alone, is the new baseline. Having a backup country is no longer enough; you need a network.

Manufacturing diversification in 2026 is driven by three pillars: resilience, speed, and flexibility. Energy reliability and regional networks are now central to supplier selection, not afterthoughts.

Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia each offer distinct advantages and trade-offs as alternative manufacturing countries. The right mix depends on your product category, risk profile, and growth plan. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer.

Successful buyers treat their footprint like a portfolio. They map risks, design a country mix, pilot in new markets, and invest in on-the-ground expertise instead of relying on remote control. The companies winning in 2026 are the ones who started planning in 2024.

How MoveToAsia Can Support Your Diversification Journey

The days of relying on a single country to manufacture or source your products are over. In 2026, resilience means multiple options, regional networks, and partners who understand both the big picture and the local reality.

MoveToAsia acts as that bridge for international buyers who want to diversify into Asia, with a strong focus on Vietnam and a network of strategic partners across the region. In practical terms, this can mean assessing whether your current product range is a good fit for Vietnam or another Southeast Asian market, identifying and vetting factories for OEM or ODM projects, organizing factory visits and audits, setting up quality control processes that protect your brand when you can’t be on site, and supporting long-term ramp-up from first orders to sustained production.

In other words, you don’t need to navigate the shift beyond China plus one alone. With the right local team, manufacturing diversification becomes a structured project instead of a risky leap. If you’re ready to start building your China +N strategy, or if you’re already underway and need local expertise to make it work, reach out to our team. We’re here to help you turn strategy into reality.